While You Weren't Looking

From Scarcity to Deluge

In 1809, Scottish botanist Robert Brown (father of Brownian motion) spent four painstaking years collecting plant specimens across Australia for Joseph Banks. Travelling with him was Austrian illustrator, Ferdinand Bauer, who created masterpieces such as this Swamp Lily.

Every one of their 1500 samples required careful pressing, drying, and illustration. Brown and Bauer’s meticulous work revealed over 100 new genera: plants that had never been taxonomically classified.

Their buildup of knowledge was glacially slow: two men, thousands of miles from scientific institutions, methodically documenting a continent’s flora specimen by specimen.

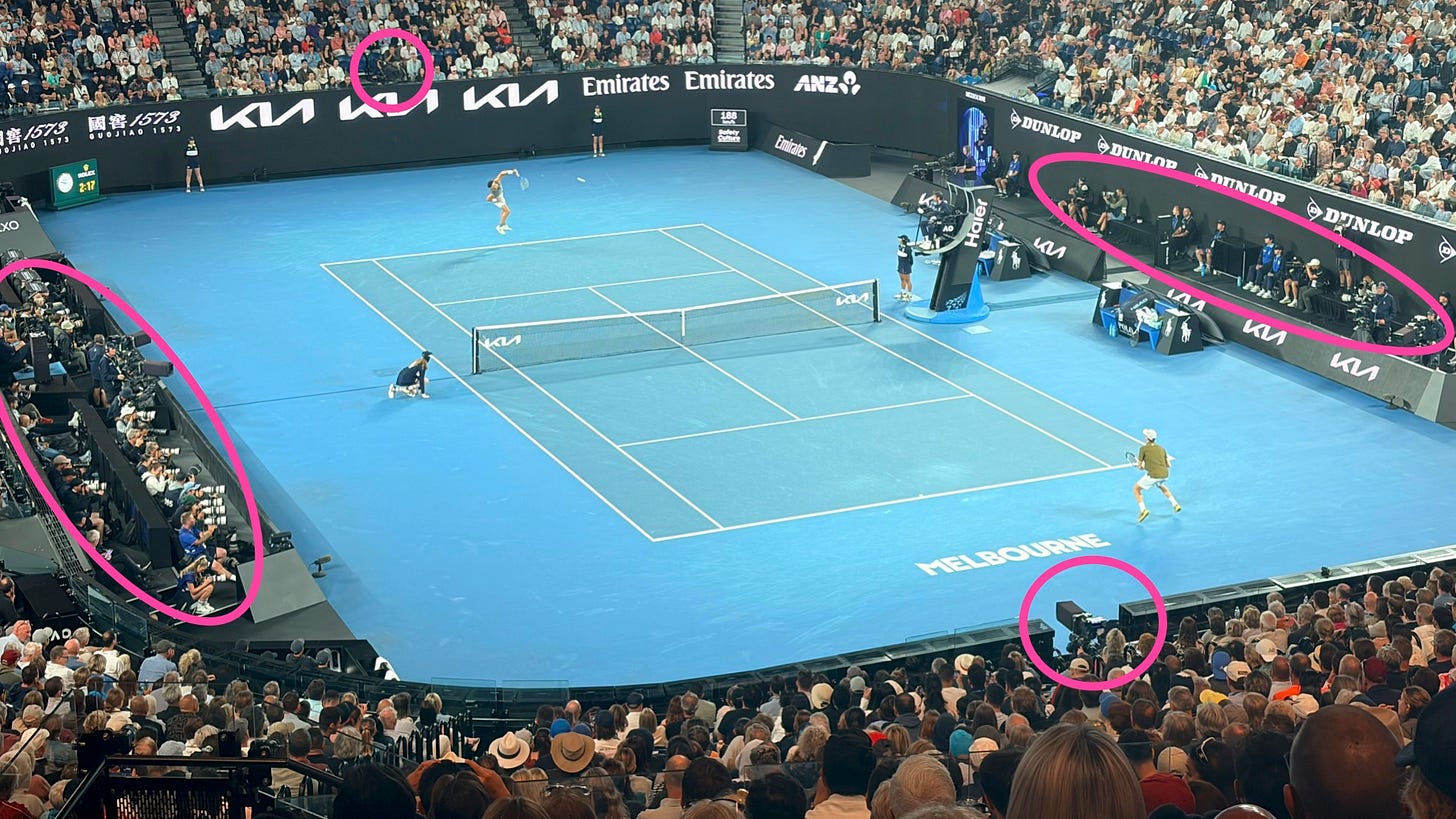

Compare that speed to a single moment at this week’s Australian Open tennis. World #8 Ben Shelton belts down a 220km/h serve to World #2 Jannik Sinner. That one stroke is captured by dozens of devices (in pink below): cameras, multiple video angles, ball-tracking technology, biometric sensors, and a phalanx of sports journalists logging every detail.

In 200 years, we’ve moved from data scarcity to data deluge.

Brown’s challenge was accumulation: gathering enough specimens to see patterns emerge across species. Our challenge is discrimination: finding meaningful signals in the simultaneous capture of everything. Banks wanted taxonomy, to understand what exists and their relationships. We want taxonomy too, but also prediction: what patterns emerge, what happens next, what advantage we can extract.

The best strategic leaders I work with have developed what I’d call “real-time sense-making capacity”. They’ve built systems that filter, prioritise, and surface the signal before the next wave arrives. They’re not spending a year with one dataset like Brown; they’re building the muscle to make sense of continuous flows in compressed timeframes.

Question: What would it take to build your organisation's capacity for real-time sense-making from the data streams you're already capturing?

Knowing What’s Coming

Mind reading is real.

Really. Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) now exist that translate human thoughts into commands for external technology. It’s not a consumer-grade product (yet!), but BCIs already help people with severe paralysis communicate and control devices with their thoughts alone.

And, it’s an Australian company that’s a global leader. Synchron, founded by University of Melbourne professors in 2012, developed a BCI that doesn’t require cutting open your skull. Their “Stentrode” device threads through blood vessels, inserted via your jugular vein, like placing a cardiac stent. Today, ten patients with severe paralysis use it at home to text, email, and control devices. So, yes, early days, but when Elon Musk was asked about Synchron in 2023, in relation to his own business, Neuralink, he conceded they’re “kicking our ass.”

Here’s why this matters for strategy.

Synchron appears in Australia’s Critical Technology Tracker, which monitors high-impact research across 74 frontier technologies: not just BCIs, but geoengineering, generative AI, advanced energy systems. The tracker reveals which countries are leading research that will translate into future capability. China leads in 66 of the 74 technologies, the USA in 8. I knew China was dominant; I didn’t expect that dominant.

So what does this mean for those of us running — or advising — organisations?

The smartest leaders I work with aren’t simply watching these developments, they’re actively asking what becomes possible when these technologies mature. A disability services team I worked with designated someone to scan emerging research quarterly. Not to become experts, but to ask: “If brain-computer interfaces become as common as pacemakers, what assumptions about independence need revisiting? What service models become obsolete?”

Question: Which research areas can expand your organisation’s sense of what’s possible for the people you serve?

Building Knowledge in Layers

35 years ago, I was matching jobseekers with employers. To do this, I needed to understand psychology: what drives people (both employers and employees), what stops them, how to read what’s unsaid.

Then, 5 years later, I moved into training and suddenly needed to understand different things: how adults actually learn, not just what motivates them. 25 years ago, as I started training leaders more than workers, I found myself needing to understand way more: about leadership, people management, change.

Then, about 15 years ago, I started advising on strategy. That meant dramatically boosting my knowledge of commercial realities, systems thinking and even macro-economics. I couldn’t help organisations see around corners without understanding how money flows and what forces are reshaping their part of the game board.

What I can see from my vantage point now is that each of these knowledge phases didn’t replace the last: it compounded and layered, creating a kind of strategic 3D-ultrasound.

When I ask, my clients tell me the same thing of their ‘knowledge journeys’.

One newly-appointed CEO told me recently she spent her 20s obsessed with people skills (she trained as a social worker). Her 30s were spent learning how businesses actually work. Now, in her 40s? AI capability and political risk. She says, “I can’t make our next big call without understanding which capabilities will migrate to machines and what happens when governments’ policy positions fragment”.

She wasn’t collecting knowledge for credentials; she was hunting for what would let her see what others couldn’t.

Question: What’s the knowledge domain just outside your current expertise that would unlock the next five years?

Until next week, keep scanning the edges, and stay curious about what’s just outside your frame.

The heart below is inside your frame, so please move the finger / cursor a few millimetres and click it. It does mean a lot to me and the algorithms that bring this to you each week.

See you next Friday,

Andrew

I really like the phrase in your first vignette – “real-time sense making” in the context of complex adaptive systems where it’s less about prediction and more about real-time sense making in the face of emergence.

Far out re China’s 66 out of 74!

In ‘Building Knowledge’ and the way you described your learning journey and that of the new CEO, I suspect that you are both super-learners, aka learning junkies. My anecdotal data would suggest that there’s not many of you in the adult population – those driven by insatiable curiosity and literally addicted to learning, both within and outside of your existing knowledge domain. According to Dr Theo Dawson, as we move through adulthood, most of us settle into one, maybe two, developmental silos, gaining deeper and richer knowledge and skills in one or two relatively narrow areas of expertise.

Another excellent, timely, thought provoking newsletter Andrew. Cheers